Detection of estrus (heat) is often cited as the most costly

component and undoubtedly, the major limiting factor to the success of A.I. programs on many dairy farms. Incorrect detection

of estrus is related to loss of income due to extended calving

intervals, milk loss, increased veterinary cost, increased heifer

rearing cost, and slowed genetic progress. To achieve excellent

heat detection, many factors have to be taken into account. First,

the cow must express behavior and physiological changes, and

secondly, these changes must be detected to determine if and

when insemination should occur. It is clear that an excellent

rate of heat detection is vitally important. Some herds have

exceptional fertility while others struggle with conception rates,

calving intervals, pregnancy rates and other parameters, which

might be caused by inefficient heat detection. Numerous factors,

environmental, managerial, and cow-related, play a role in

estrus expression and detection. Many devices are commercially

available to assist with heat detection and each producer must

decide which works the best in their dairy. The time of ovulation

and age of the egg at sperm penetration is critical for conception,

so the goal of a heat detection program should not merely be to

attain a high detection rate but to achieve a high detection rate

with a corresponding high conception rate.

Detection of estrus (heat) is often cited as the most costly

component and undoubtedly, the major limiting factor to the success of A.I. programs on many dairy farms. Incorrect detection

of estrus is related to loss of income due to extended calving

intervals, milk loss, increased veterinary cost, increased heifer

rearing cost, and slowed genetic progress. To achieve excellent

heat detection, many factors have to be taken into account. First,

the cow must express behavior and physiological changes, and

secondly, these changes must be detected to determine if and

when insemination should occur. It is clear that an excellent

rate of heat detection is vitally important. Some herds have

exceptional fertility while others struggle with conception rates,

calving intervals, pregnancy rates and other parameters, which

might be caused by inefficient heat detection. Numerous factors,

environmental, managerial, and cow-related, play a role in

estrus expression and detection. Many devices are commercially

available to assist with heat detection and each producer must

decide which works the best in their dairy. The time of ovulation

and age of the egg at sperm penetration is critical for conception,

so the goal of a heat detection program should not merely be to

attain a high detection rate but to achieve a high detection rate

with a corresponding high conception rate.

BEHAVIORAL CHANGES

The occurrence of estrus is due to specific influences of ovarian

steroid hormones on behavioral centers in the brain. As a growing

follicle matures under the stimulation of follicle-stimulating and

luteinizing hormones (FSH and LH) during the last three to four

days of the estrous cycle, it synthesizes and secretes increasing

quantities of estradiol. A threshold level of estradiol is reached

which triggers two closely linked events – the behavioral

response known as estrus and a surge of pituitary hormones,

primarily LH.

It is useful to point out that the maturity of the Graafian

follicle that regulates the amount of estradiol synthesized

regulates its own time of ovulation and concurrent maturation

of the oocyte.

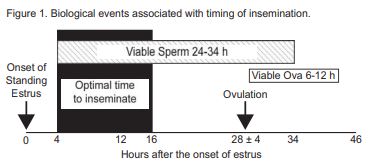

Traditionally, the cow that stands still and allows others to

mount her is in “standing heat.” Standing is the primary sign

of estrus. Ovulation usually occurs approximately 24 to 32

hours after the onset of standing estrus in dairy cows. After

ovulation, there is only a short period when ova can be fertilized

(Figure 1). Optimal fertility of ova is projected to be between six

and 12 hours after ovulation. The viable life span of sperm in the

reproductive tract is estimated at 24 to 34 hours.

The average period of “standing heat” is usually less than

10 hours and consists of about one standing event per hour.

Secondary signs of heat may be an indication that the cow may

soon display standing estrus, is currently in estrus, or has already

gone out of standing heat. Since the degree of these advanced

signs vary in length and intensity, a combination or having

multiple secondary signs increases the reliability of the decision to

breed. It can also help to increase the amount of cows submitted to

A.I. by allowing the insemination of cows that cannot be detected

otherwise.

Secondary signs are caused by elevated levels of estrogen on

the day the animal is in heat. They are also most likely caused by estrus-related activities and events. The primary sign of estrus

is a cow standing to be mounted by another cow(s) even though

she could have resisted the mounting activity. The reason why

secondary signs of estrus get this name is they can also be

caused by events other than estrus and are secondary to standing

to be mounted as the definitive sign. Therefore, a single secondary

sign of estrus should not be enough to make the decision to

inseminate; if a cow is not seen standing to be mounted and is

suspected in estrus, it will be necessary to have a combination of

secondary signs to confirm that the cow is really in estrus. Below

are some of the most commonly recognized secondary signs of estrus.

• Rubbed marks – When a cow dismounts another, she slides

down her tail head and rump. Therefore she puts

considerable pressure on the pin bones and backbone, and

this repeated abrasive action pulls out hair and may produce

red, bloody or swollen sores. Size, appearance, and freshness

of these marks along with the fact that few other events

can cause similar signs; these rubbed marks are one of the

most reliable secondary indicators of estrus. Additionally,

you may find that the flanks of the cow in question have dirt

or manure marks from the hooves of other cows riding them

and are another indication that riding events have recently

happened.

• Mucus – Many technicians would state that mucus is the

most liked secondary sign of estrus. Experienced

inseminators put a profound credence on this sign when

deciding to breed or not to breed a cow, and sometimes they

even massage the cervix and anterior vagina to express a

mucus discharge. Discharged mucus dries quickly so finding

dried mucus on the tail, flanks, or legs is just as good a

secondary sign as seeing a string of clear viscous mucus

coming from the vulva.

• Sweaty appearance – Some cows will develop a sweaty

appearance when in estrus. This “wet” appearance, even

though it is easily detected, is frequently overlooked and may

be where the slang term “hot” cow originated.

• Swollen vulva – Rapidly growing follicles produce high

circulating levels of the hormone estrogen that increase

blood flow to the reproductive tract. The vulva increases in

size and takes on a pinkish swollen appearance. Upon

opening the labia an intense dark pink to red and highly

moistened vagina is present if the cow is in estrus. In

contrast, the vagina will appear dry and pale to white in color

when the cow is not in estrus.

• Chin resting – Chin resting is thought to be testing by herd mates to determine if an individual is receptive to being

mounted. This testing is performed by first resting a chin on

the back of the cow. Considerable salivating and licking

usually takes place during this testing process so you should

inspect the loin and tail head area for saliva.

• Bellowing and urination – There is a tendency for increased

urination. The cow will begin holding her ears erect, become

restless and nervous. Cows coming into heat will become

more active and will spend more time walking around

rather than lying down chewing their cud. Be aware that

during movement, like to and from the milking parlor, is an

ideal time for a cow to mount another and therefore a great

time to detect mounting activity. Some cows may appear to

be standing when in fact they just couldn’t get away because

of crowding. Extra care should be taken to avoid false

positives like this one.

• Bloody discharge – A streak of blood in the mucus usually

means that that cow had a high peak of estrogen one to three

days ago. It is therefore recommended to record that heat

and date it two days ago. This only indicates that she has

been in heat. It has no relationship with timing of ovulation

or whether or not she conceived.

• Grouping – Cows in heat tend to look for willing partners to

get involved in estrus-related activities. These sexually active

groups are a clear indication that at least one cow inside one

of these groups is in estrus.

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE DETECTION

Cow factors

• Heritability – The heritability of estrus expression is very

low and varies between cows, even for the same cow, from

one estrus period to another. Just because a cow is very

active today does not mean she will be at her next estrus

period during this lactation or in subsequent lactations.

However, there are differences between breeds. In general,

Jersey cows and heifers have more intense and longer

periods of estrus expression than Holstein cattle.

• Days in milk – Silent heat (more correctly, silent ovulation),

is common at the first ovulation after calving. Progesterone

released from the corpus luteum (CL), formed after the silent

ovulation, appears to favor estrus expression during the next

cycle.

• Lactation number – A report from Spain in 2006 revealed

a 21 percent decrease in walking activity with each

additional lactation. A study from the United Kingdom in

2009 reported a significant increase in walking activity

during estrus for heifers versus first lactation cows, and a

significant decrease between first and later lactations, but

no difference in walking activity during estrus for cows

between second and later lactations.

• Milk production – There is no correlation between estrus

expression and milk yield; however, the metabolic clearance

of steroid hormones related to high milk production probably

reduces behavioral expression of estrus. In a study with 267

lactating dairy cows, cows with daily milk yield greater than

57 lbs. (39.5 kg) per day had lower blood estrogen levels and

shorter duration of estrus than herdmates producing less

than 87 lbs. (39.5 kg) of milk daily.

• Lameness – Lameness is classically associated with a

reduction of estrus intensity. Lame cows spent more time

lying and less time standing and walking during estrus. One

study reported an overall reduction of approximately 37

percent in estrus intensity for lame cows.

• Hormonal treatments – Progesterone increases the

sensitivity to estrogen and usually results in increased

estrus expression, specifically mounts, chin resting, and

sniffing (which may explain why after removing a CIDR®

insert, increased estrus expression is common). In contrast,

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) reduces or

suppresses the expression of estrus by causing the early

ovulation of the developing follicle prior to peak estrogen

levels that prompt the expression of estrus.

Environmental factors

• Season – Most studies have reported a depression in estrus

expression during extreme temperatures, either hot or cold.

The inability to have a period of recovery from high

temperatures during the day has also been reported to

negatively affect estrus behavior. Heavy rain, strong wind,

and high humidity also reduce or suppress estrus behavior.

• Nutrition – Loss of body reserves (negative energy balance)

can negatively affect estrus expression. The presence of

mycotoxins, especially vomitoxin and zearalenone, reduce or

suppress estrus expression.

• Housing – The type of floor surface affects estrus behavior.

Duration of estrus and number of mounts were longer (13.8

versus 9.4 hours) and greater (7 versus 3.2 times) on dirt

than on concrete surfaces. Covering a concrete grooved

floor with perforated rubber mats improved the ability of

cows to express normal behavior activity.

• Herd size and over-crowding – The number of social

interactions between cows is greater when the herd size is

larger. However, over-crowding will reduce expression

of estrus by limiting the space available for socially active

groups to form and interact. The degree of estrus expression

and therefore, the possibility of detection, can be

dramatically favored by the number of cows in estrus

simultaneously. This is the reason PGF injections work to

increase detection, especially prior to first insemination.

Each additional cow in heat at the same time has been

associated with a six percent increase in walking activity.

Records

A good record keeping system is one of the most valuable

tools in any detection program, mostly because it will increase

the accuracy of your decisions. All heats must be recorded even

if the cow is not bred at that heat. The pivotal question is when

the last insemination occurred. Having an interval of 18 to 24

days makes the decision to inseminate easier. Breedings that

occur with an estrus interval of four to 16 days usually result in

less than desired conception rates and should be avoided unless

the secondary signs strongly sway the decision to inseminate.

Also knowing if the previous breeding was a result of timed A.I.

or from a standing event may alter the decision. These off-cycle cows could be palpated for the presence of a clear stringy

mucous as the final and definitive secondary sign to confirm the

decision to inseminate.

TIMING OF INSEMINATION RELATIVE TO ESTRUS

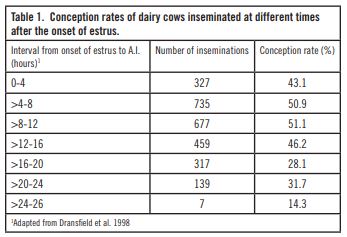

For the past 65 years, researchers have investigated the

optimal time at which to inseminate cows relative to the stage

of estrus.  Trimberger (1948) found that conception rates were

highest when cows were inseminated between six and 24 hours

before ovulation. This early work led to the establishment of the

a.m./p.m. recommendation. This guideline suggests that cows

in estrus during a.m. hours should be inseminated during the

pm hours, and cows in estrus in the p.m. should be bred the

following a.m. However, research with large numbers of cows

indicates that maximum conception rates may not be achieved

using the a.m./p.m. recommendation. A large field trial (44,707 cows) found no difference in the

percentage of non-return rates at 150 and 180 days (which

would indicate pregnancy) between cows bred either the same morning as observed estrus, between noon and 6 p.m. on the

day of observed estrus, or cows bred the following morning after

observed estrus the previous evening. This indicates that a

single mid-morning insemination for all cows observed in estrus

the night before or the same morning should yield acceptable

conception. Also, cows bred once daily (between 8 a.m. and

11 a.m.) had similar non-return rates as cows bred according

to the am/pm guideline. When knowing the onset of standing

behavior, research suggests that cows be bred earlier than the

a.m./p.m. guidelines. Highest conception rates for A.I. occurred

between four and 12 hours after the onset of estrus (Table 1). Cows inseminated 16 hours after the onset of estrus had lower

conception rates than cows bred between four and 12 hours after

the onset of estrus.

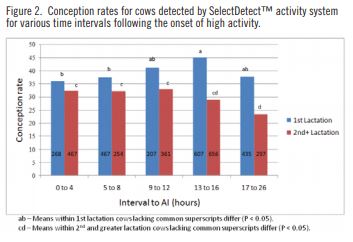

The effects of interval to A.I. on conception rates of dairy cows

(4,126 breedings) having high activity using the SelectDetect™

activity system were consistent with similar studies based on

observed mounting activity (Figure 2). he mean duration of

high activity was 10.5 hours with a median of 10 hours. Among

first lactation cows (Figure 2), optimum conception occurred

at A.I. intervals of eight to 16 hours after the onset of high

activity and trended lower for both earlier and later A.I. intervals.

Trimberger (1948) found that conception rates were

highest when cows were inseminated between six and 24 hours

before ovulation. This early work led to the establishment of the

a.m./p.m. recommendation. This guideline suggests that cows

in estrus during a.m. hours should be inseminated during the

pm hours, and cows in estrus in the p.m. should be bred the

following a.m. However, research with large numbers of cows

indicates that maximum conception rates may not be achieved

using the a.m./p.m. recommendation. A large field trial (44,707 cows) found no difference in the

percentage of non-return rates at 150 and 180 days (which

would indicate pregnancy) between cows bred either the same morning as observed estrus, between noon and 6 p.m. on the

day of observed estrus, or cows bred the following morning after

observed estrus the previous evening. This indicates that a

single mid-morning insemination for all cows observed in estrus

the night before or the same morning should yield acceptable

conception. Also, cows bred once daily (between 8 a.m. and

11 a.m.) had similar non-return rates as cows bred according

to the am/pm guideline. When knowing the onset of standing

behavior, research suggests that cows be bred earlier than the

a.m./p.m. guidelines. Highest conception rates for A.I. occurred

between four and 12 hours after the onset of estrus (Table 1). Cows inseminated 16 hours after the onset of estrus had lower

conception rates than cows bred between four and 12 hours after

the onset of estrus.

The effects of interval to A.I. on conception rates of dairy cows

(4,126 breedings) having high activity using the SelectDetect™

activity system were consistent with similar studies based on

observed mounting activity (Figure 2). he mean duration of

high activity was 10.5 hours with a median of 10 hours. Among

first lactation cows (Figure 2), optimum conception occurred

at A.I. intervals of eight to 16 hours after the onset of high

activity and trended lower for both earlier and later A.I. intervals.

Among second lactation and older cows, conception rates were

similar until 16 hours after the onset of high activity. Optimum

conception rates were obtained at A.I. intervals proximal to 12

hours after detected estrus with shorter intervals appearing

to be less compromising to conception rates that are of longer

intervals.

Among second lactation and older cows, conception rates were

similar until 16 hours after the onset of high activity. Optimum

conception rates were obtained at A.I. intervals proximal to 12

hours after detected estrus with shorter intervals appearing

to be less compromising to conception rates that are of longer

intervals.

WHEN SHOULD DAIRY COWS BE INSEMINATED?

The traditional a.m./p.m. recommendation works best with

twice daily observations but may not provide the best conception

rates because several cows will be bred too long after the

onset of estrus, so the chance for successful fertilization may

be missed. The exact onset of estrus is usually unknown. For

example, according to the a.m./p.m. guideline, a cow beginning

estrus at 1 a.m. and observed in estrus at 6 a.m. would be bred

approximately 18 hours after the onset of estrus. Breeding cows

at this time would reduce the number of cows that become

pregnant (Table 1). Cows should be inseminated within four to

16 hours of observed estrus when the precise onset of estrus is

known (Figures 1 and 2). If estrous detection is conducted twice

daily, most cows should be within this time period. However,

a single mid-morning insemination of cows that have been

observed in estrus the same morning or the previous evening

should provide acceptable conception rates.

SUMMARY

Traditionally, the cow that stands still and allows others to

mount is in “standing heat.” Standing is the primary sign of

estrus and determines the time of insemination since ovulation

occurs 25 to 30 hours after the onset of standing activity.

Secondary signs of estrus may be an indication that the cow

may soon display standing heat, is standing now, or has already

gone out of standing heat. Since the degree of these advanced

signs vary in length and intensity, a combination or having

multiple secondary signs increases the reliability of the decision

to breed. Making the decision to inseminate often will require the

use of secondary signs of estrus. There is a fine line that will only

come with experience when using secondary signs to make the

decision to breed or not to breed. Because of biological variation

in the time of ovulation in respect to the onset of estrus, sperm

transport time in the female reproductive tract to the site of

fertilization, and life span of both gametes (sperm and ova) there

is a broad window for the optimum time of A.I., of approximately

12 hours. The key component to timing of A.I. is frequent and

accurate observation periods to determine the onset of estrus.

PDF IN ENGLISH

PDF en español

™Select Reproductive Solutions is a trademark of Select Sires Inc. Product of the USA SS106-0714

®CIDR is a registered trademark of Pfizer Inc.